January 22, 2018 – Xiamen, Fujian Province

“You can’t get there from here,” the woman at the ticket window said.

She did not look up at my outstretched arm, pointing across the bay. Nothing in her face moved, except for her lips. I stood for a moment and watched the boat docked “here” fill up with people, then rumble away, the start of a roughly five minute journey to “there”.

I turned back to the ticket woman, who still hadn’t moved her eyes from whatever was just below the window, out of my view, and I started to protest, having seen the boat go exactly where I wanted to go. She cut me off.

“You have to go to a different dock. Cross the street, then get on Bus 58. Go to the other dock.”

I sat down on a ledge not far away from “here”, and watched the cross-bay ferry arrive “there:” Gulangyu Island.

Gulangyu is a tiny, pedestrian-only island across the bay from Xiamen’s old town. The 2-square-kilometer island is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, attracting more than 10 million visitors a year who want to wander the lanes that wind past Victorian-era European-style villas, consulates, police stations and churches, many of them (at least I’m told) now converted into coffee shops and B&Bs.

Gulangyu once was a foreign island among a sea of Chinese. After the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842 that opened up both Fuzhou and Xiamen to foreigners, nationalities from across the world settled on Gulangyu, administering it with an independent governing council. Thirteen countries took part in its administration before Japan took it over entirely during World War 2, and for decades the British Empire’s Sikh police force from India patrolled the settlement.

My plan to take a ferry to an island for a mini vacation had fallen apart, and instead of relaxing anywhere, I’d spent two full days stuffed into the seat of one metal box or another. I had one last chance to make something of my island plan, even if were for only a few hours before we had to catch the train to Fuzhou to catch the bus to the airport to catch the flight to Tianjin to catch the train back to Beijing to catch a cab home.

But “here” I was, sitting on the dock. Again.

I’d been thrilled the night before to discover that our hotel lay just up the street from this dock on the bay, across which, in the dark, a cherubic light illuminated the hilltop church as if it were the painted head of a some medieval saint.

If Gulangyu is a Cavallini, Xiamen’s old city, then, is a Picasso, a jarring and disjointed amalgamation of geometries that together make an almost coherent, maybe beautiful whole.

Xiamen’s newly rebuilt main old town shopping street is a white-blasted assault, European buildings juxtaposed against the international and Chinese brand name stores fitted into their lower levels and people everywhere. But outside this artery, a network of capillaries branches out like spider veins, and it’s in there one can find the lifeblood of the city.

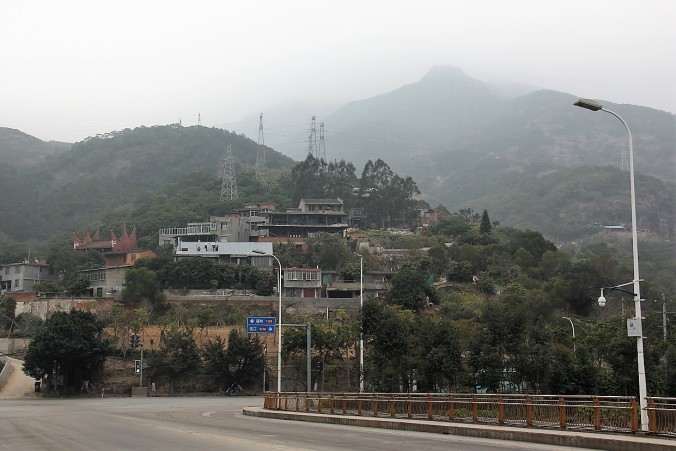

Xiamen Old Town

These vessels narrow, some to just shoulder width, and overhead, buildings and wires twist upward, competing for space, all of them colonized by moss-like laundry drying slow in the humid air. Open doors face the street, and families laugh over dinner in front of LCD televisions on sterile floors below their loft beds. Up that way, the Buddha’s face shines down the stairs, concealed by a whole garden of plants. Down this way, a man fries noodles for a customer through a cloud of shifting steam and smoke, while his grandfather in the back rustles Mahjong tiles with the neighbors. One doorway leads into a hotel, while another one opens into a convenience store and another into a schoolyard.

Some of these veins pour out into community parks, complete with a stage, a library, some art. Other veins flow back into the arteries, where crowds jostle for seating at Vietnamese restaurants or red-paper shops. Some veins empty into the local seafood market, where vendors shout through cigarette-stuffed lips at passersby, trying to sell one last octopus, crab, or turtle before they pack up their stalls, and sling water into the street to wash up the blood, scales, and guts. By daylight, fresh hauls of shrimp, eels, and shark will fill the street, along with the cacophony and the smell.

We spent the night swimming these lifelines, then biked through the burgeoning art and bar district before settling in to chat with the owner-brewer at Fat Fat Beer Horse about life in Xiamen (he likes it). By the time we biked back it was near 1 a.m., but I still planned to make it to the morning ferry. At least the walk to the dock was short.

Or so I’d thought, before I stumble trudged toward Bus 58, lids heavy, to take it to “the other dock”, wherever that was.

I got off the bus 20 minutes later. I’d seen a sign for “To GulangYu”, and I walked up to the ticket window at an even smaller dock than the first.

“Gulangyu,” I said. “One ticket.”

“Do you have the card?” she asked.

“What card?”

“So you’re a tourist. You can’t take this boat. You have to take the tourist boat. The local boat is 8 yuan. The tourist boat is 50. You can’t take this one. You don’t have the card.”

“But how do I get to the tourist boat?” I asked, after a sigh.

“Take bus 58.”

I wanted to scream. As I pedaled lethargically back to where I started, I was ready to give up.

No more boats for me.

I passed the stop where I’d first boarded Bus 58. I stopped and watched as the bus pulled in. People loaded on.

No, I thought. No more boats.

I looked across the bay at the island, the church high above the trees, tree which hid all but the peaks of those colonial buildings. I imagined walking under those trees gazing at history as I strolled, winding my way up the hill to the church — no bikes, no cars — and looking back toward Xiamen and its skyline. I imagined sipping a black coffee and sitting in the warm winter sun, gazing out over the sea. I ran to catch the bus.

I rode Bus 58 to its last stop. I arrived, finally, at the tourist ferry terminal. The boat tickets were sold out. I turned around and started my day-long journey back to Beijing.

Being watched at the Xiamen train station.